Words and things are no longer linked together.

Have you ever happened to catch strange coincidences while creating something?

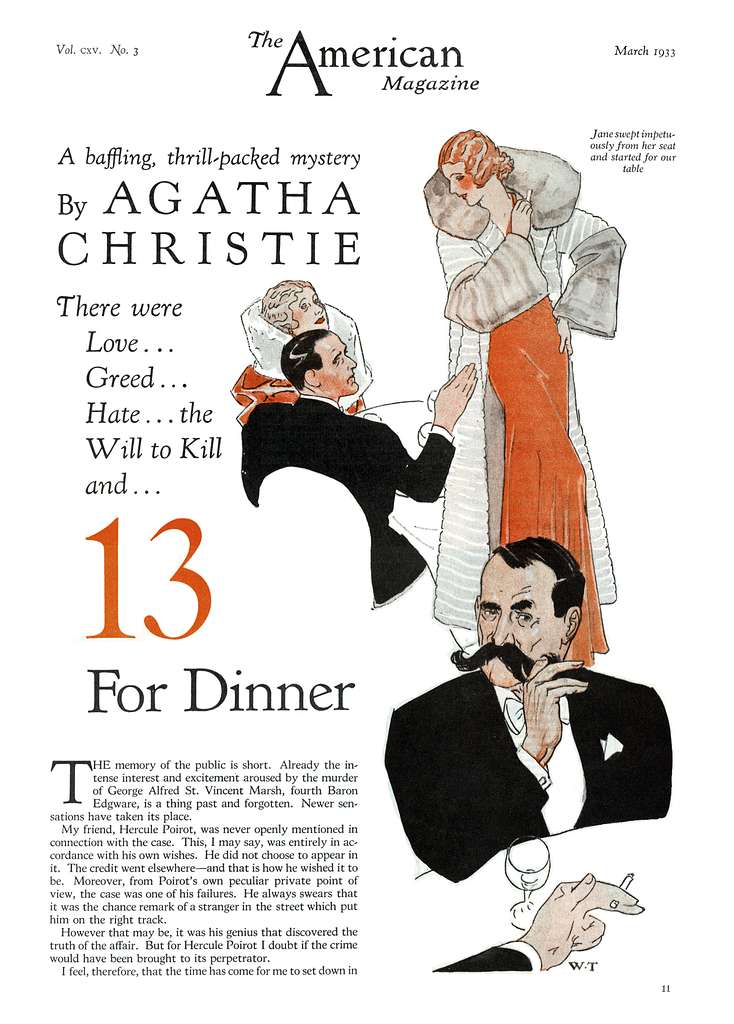

It happened to me starting with Poirot, Agatha Christie‘s famous character.

Hercule Poirot is a Belgian refugee who lands in England as a private investigator.

He is a man “not tall, plump, little hair, the famous upturned mustache, elegant and refined, loves perfection and order.”

Poirot has something eccentric and out of the norm while in absolute control of movement and communication.

Habitual, calm, methodical, manic, sometimes boring. But with flashes of intelligence out of the ordinary.

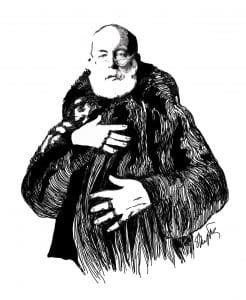

And if we want to talk about brilliant investigations, how can we not remember Maigret, a character invented by George Simenon, a great Belgian writer.

Simenon does not appear to us as a very visible writer, yet behind that methodical and calm appearance lies a very prolific novelist who often changed residence between Belgium, Canada, the United States, France, and Switzerland. An unstable and very eventful private life, but in everyone’s eyes it is the novels that are the author’s real adventures. Yet the author himself will use many personal experiences to write his books.

And what about his famous character Maigret.

He does not resemble conventional policemen. He wears well-cut clothes, shaves carefully and has manicured hands. But the appearance is massive, plebeian.

Unlike the author, the character is monogamous.

What distinguishes Maigret’s investigations? The pipe. Which also gives the title to a 1947 short story.

Pipe that we find celebrated and immortalized by another world-famous artist who is Renè Magritte.

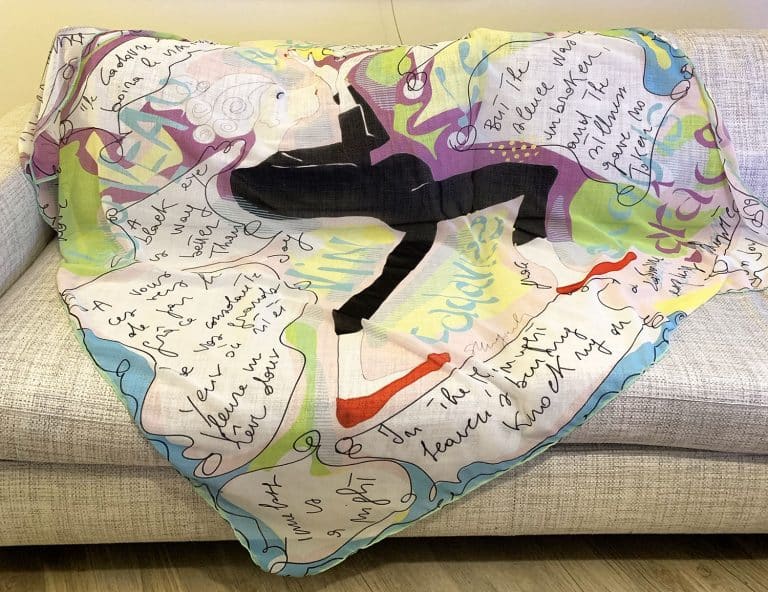

Alongside the best-known depiction of the man dressed in black with the black bowler hat, Magritte plays on shifts in meaning.

In the same painting there is the stone as light as the cloud, or day and night, decontextualizing objects.

The stroke is cold and impersonal, methodical too. Quiet like a Poirot interpreting clues and searching for evidence.

There is an investigation of experience and representation.

Reality is not always what it seems.

Magritte is called the “quiet saboteur” for that he investigates reality by uncovering its mysteries while not solving them.

Reality and fiction: the great themes of art unfolded in a methodical and quiet life without great shocks, which was Magritte‘s.

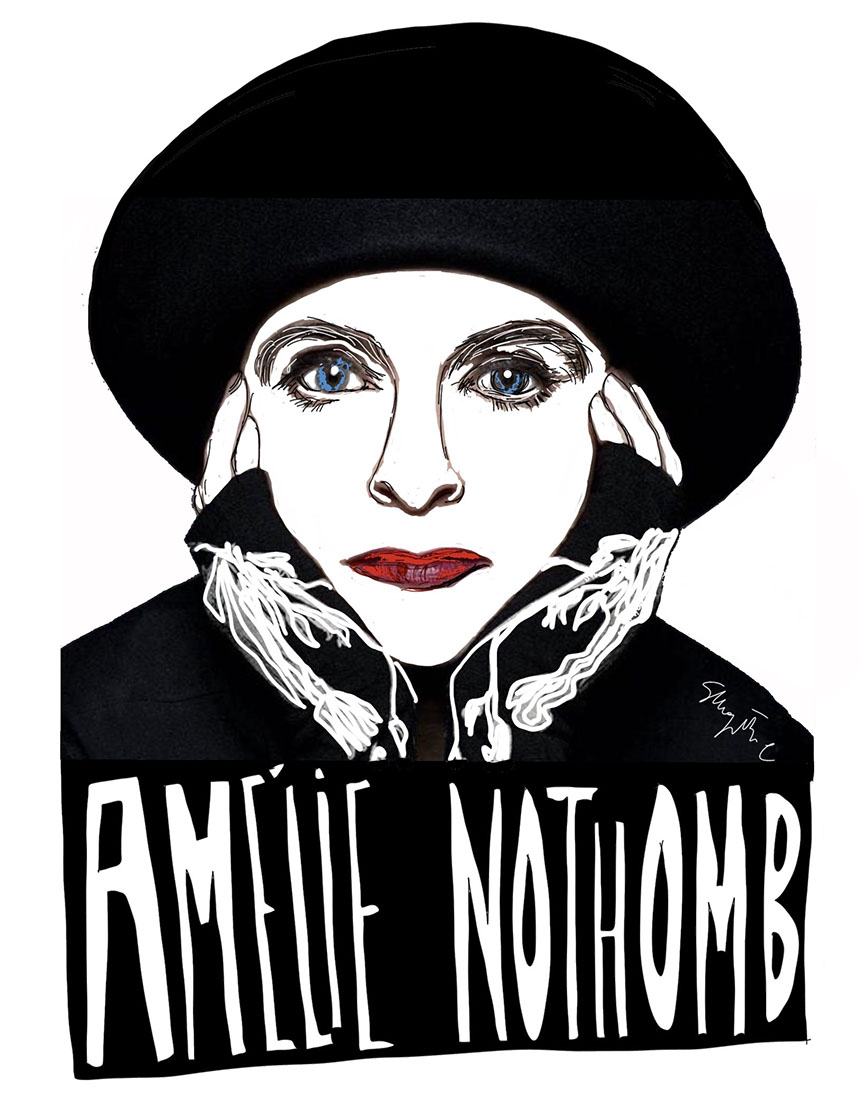

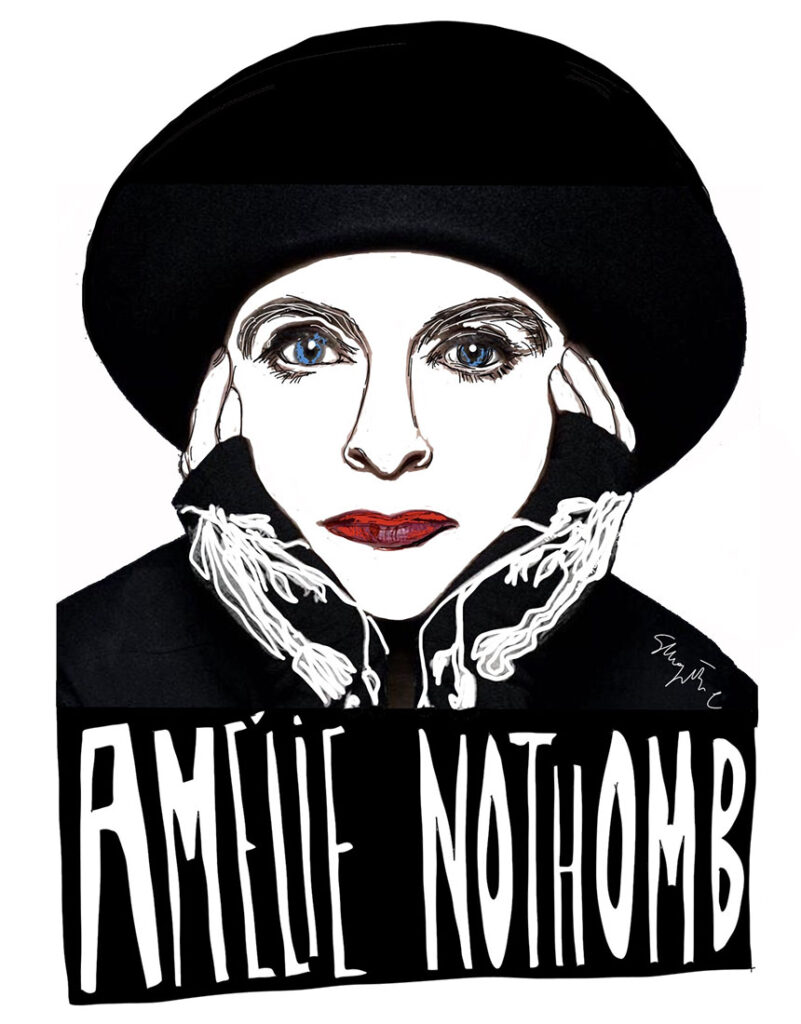

When I think of the back-to-back male figures, dressed in black, wearing bowler hats, falling like rain from the sky in some of Magritte‘s famous paintings, my thoughts turn to a contemporary writer belonging to one of the oldest and noblest Belgian families: Amélie Nothomb.

She too always dresses in black, wears eccentric black hats, and the only note of color is red lipstick.

She publishes a book every year at the end of August, always writes her books by hand, gets up every day at four in the morning and writes for four consecutive hours drinking her steaming black tea.

Recalling Magritte, she says about writing, “I work on reality: this does not mean that everything I write happened or happens in reality. However, my subjects are real.”

After all, when asked which literary current she belongs to, so as not to disappoint younger readers, she decided to find a historical reference and singled out Brussels Surrealism, which brought remarkable innovations to literature and painting in the 1930s.

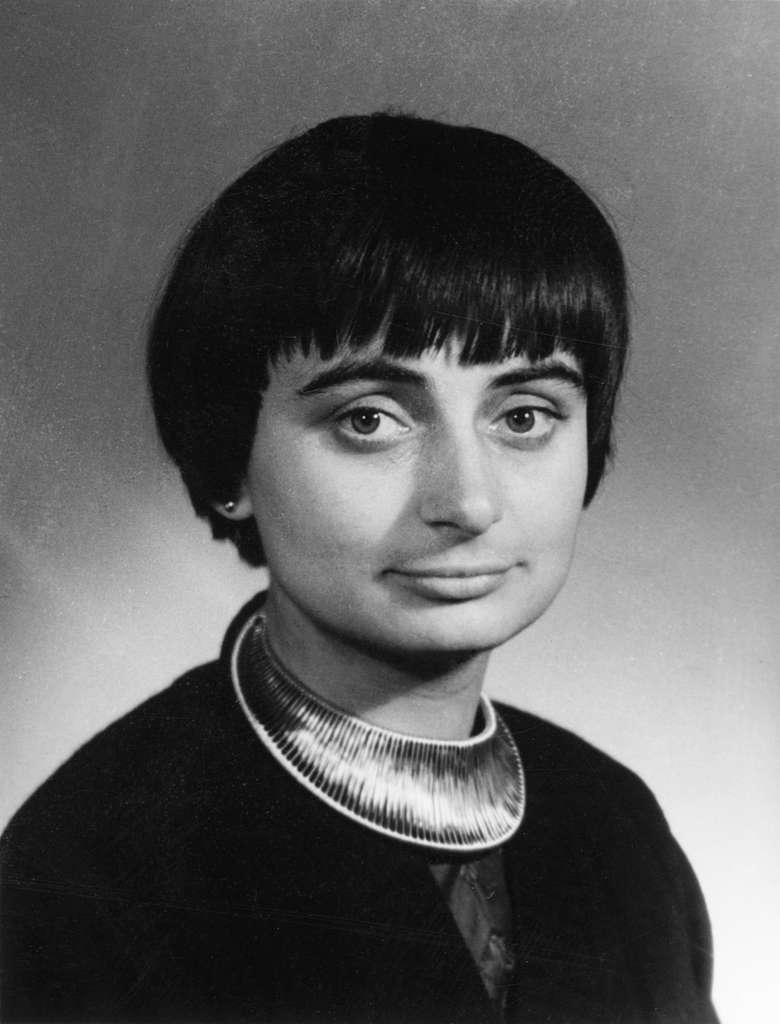

And when I think of Nothomb‘s hats that make her a fairy-tale, literary, out-of-time character, I can’t help but recall the great photographer, filmmaker and screenwriter Agnès Varda, with her distinctive bob of hair that would never change and would be an essential character trait.

“It was practical not to change. It allowed me not to struggle to be beautiful, to be young, to do better than the others. I tried to be like that, to do what I had to do.”

Agnès Varda scrutinizes reality and does a similar job to the other Belgian filmmakers mentioned above: “what interests me most is to see, so that others can in turn see as well, not only because this gives pleasure, since it is often horrible what one sees, but because it seems to me to be a contact with things. In my films I always want to “show” in a profound way. I don’t want to show but to give people the desire to see.“

The desire to see, to interpret reality.

It is certainly a common characteristic of all artists, but in all these Belgian authors there is a step backwards of the artist who although connoted by certain characteristics that never changed in their lives (pipe, hat, hair, mustache, etc.), give way to a reality interpreted artistically with an almost silent method, without jolts, without striking situations.

If I were to think of another great Belgian artist, I could not fail to mention Marguerite Yourcenar, the first woman admitted to the Académie française.

Her imagination is translated into writing with precise rules: “Writing is a job, but it is also almost a game, and a joy, because the essential is not the writing, it is the vision. I have always written my books with thought before transcribing them on paper, and sometimes I have even forgotten them for ten years before giving them a written form.”

Yourcenar writes methodically even after forgetting the initial idea for years. Not only that, she revises the text many times and each time even when everything seems fine, she keeps removing superfluous words.

She therefore writes at the foot of the page how many words he has removed. And he says, “…I am overjoyed: I have suppressed the unnecessary.“

What, then, do all these artists mentioned so far have in common?

Method, perseverance, a life little in the spotlight.

But this is certainly not enough; these are elements common to almost all artists.

Perhaps we need to search for some roots in surrealism to understand something more.

With Brussels Surrealism a new imagery was given birth. Words and things are no longer linked together.

The meaning of things changes with new pairs of meaning.

A pipe is not a pipe but a representation of a pipe, a shoe has fingers, men rain from the sky, day and night coexist on the same house.

Painting like the written word, seem real and’as well are illusory and the true meaning is diverted.

What is reality? But perhaps that is not the right question.

What reality lies behind and beyond the reality we know?

No dream images, no automatic writing.

The universe is real but filled with puzzles.

In a perpetual game, and we see it in the authors in this post, between what eyes see, images reproduce and language says.

It is doubt, the lever that makes the art of these Belgian artists unique.