Let’s start a new column: short stories about my scarves, written by writers who love what I do.

The first one is by Attilio Gatto, journalist.

(If you want to read the story in Italian, click HERE).

She let the final scarf slide over her long, slightly wavy hair, a capricious forelock offering itself to the world, rejecting the protection of that magnificent drape.

Genevieve knew she wasn’t perfect, or well-groomed. Although she was no longer quite young, she had maintained and even increased her nostalgia for the nonconformity of her twenty years.

Her husband, children, family, and job had turned her into a woman perfectly prepared to adhere to the principle of reality, to go by the rules and assume her responsibilities.

But from time to time she let herself go, spreading the wings of folly, feeling the giddiness of disobedience. And she expressed all this in the great decisions of life, but the traces, the signs were there, in the fascinating, almost imperceptible details emerging from the expressions of her face, from the language of her body and, why not, from her purposely but not overly shabby clothing of an adolescent who grew up with the name of Genevieve.

Genevieve hated everything that smacked of fashionable. She preferred vintage clothes of the 1920s and 1950s, just as she loved the old books in the stalls along the Seine. That’s where her husband had seen the crazy poster with a maddened Gerard Philipe feeding on tales and short stories, actually eating the pages and exclaiming, “Devorez des livres. Mieux qu’un cadeaux un livre!”.

It was the synthesis of an imaginary Gerard who was interpreting Modigliani, Gerard “Fanfan la Toulipe”, side by side with Gina Lollobrigida. He had to have that poster, make it his own, metaphorically make the entirety of French cinema his own.

Along the streets of Paris, they had made strange encounters; a Hemingway lookalike, a woman who appeared to have been painted by Picasso, a man smoking a pipe recalling Inspector Maigret interpreted by Jean Gabin. And all this was too similar to a magical Woody Allen film, where the Paris of today was conversing with that of a Paris of infinite pasts.

Time was annulled by space, which was still Montmartre, Montparnasse, the Luxembourg Gardens. And down there, beyond Place de La Bastille, lay the cemetery of Pere Lachaise, where the nobles of France chatted with actresses, actors and the stars of pop music.

That cemetery was more alive than a city, a world of the dead in a Tim Burton movie. And it was the Paris of the 18th-century described in Casanova‘s memoirs. As if the past, the time preceding us, was the key that could reveal the secret of an existence able to heal the wounds inflicted by a path disseminated with obstacles.

An idea of lightness fluttered in the sky above Paris and took hold of Genevieve, who was then attracted by a motionless man painted white. That man, without words, told a story that Genevieve imagined as an embryonic mime searching for his art, immobile and steadfast.

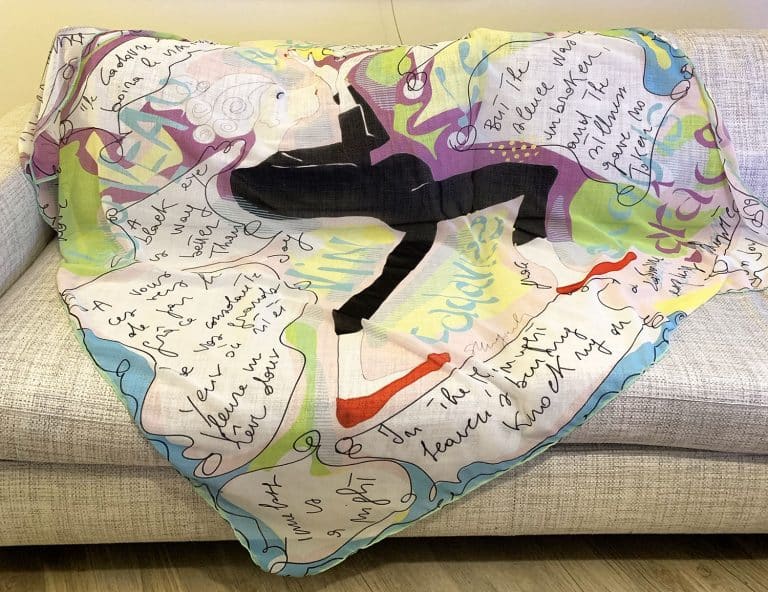

He was unhurried, awaiting the idea, the venture to create. One day he would take the first steps towards his stage and his public. Everything would come about in an instant. And in an instant Genevieve was enticed by an apparition. In an adorable boutique on Ile Saint Louis, she had seen that final scarf. She had a collection of them. She wore them as sarongs, as skirts, as shawls to cover her shoulders, as decorations for improbable handbags, as handkerchiefs for drying tears, as bandages to colour daily fears which, now she knew, needed just a little help – a red skirt with flowers or a purple hat. But that scarf from Paris was far more, it was a banner crossed by perfect whites and absolute blacks. They were bodies and faces and lines drawn by steady, expert hands. And yet she could feel the twinges of hesitation, of irresolution, as if it were the sketch for a masterpiece, an unfinished work.

Genevieve saw in it the germs she had been carrying all her life. The germs of rebellion, a never-ending search for herself, for the right distance from the laws of flattery and obsequiousness. Her husband, who knew her well, understood and asked, ”What are you waiting for?”

And the spell turned into the possession of that subjugating, mysterious object of desire. Now an Anna Magnani was observing her through the scarf, so expressive and undecipherable that she seemed the heroin of a film by Buñuel. At the end of the day, they summed it up: black and white, a little colour, a portrait, a scarf, the plot of a film ready for shooting, obviously set in Paris.