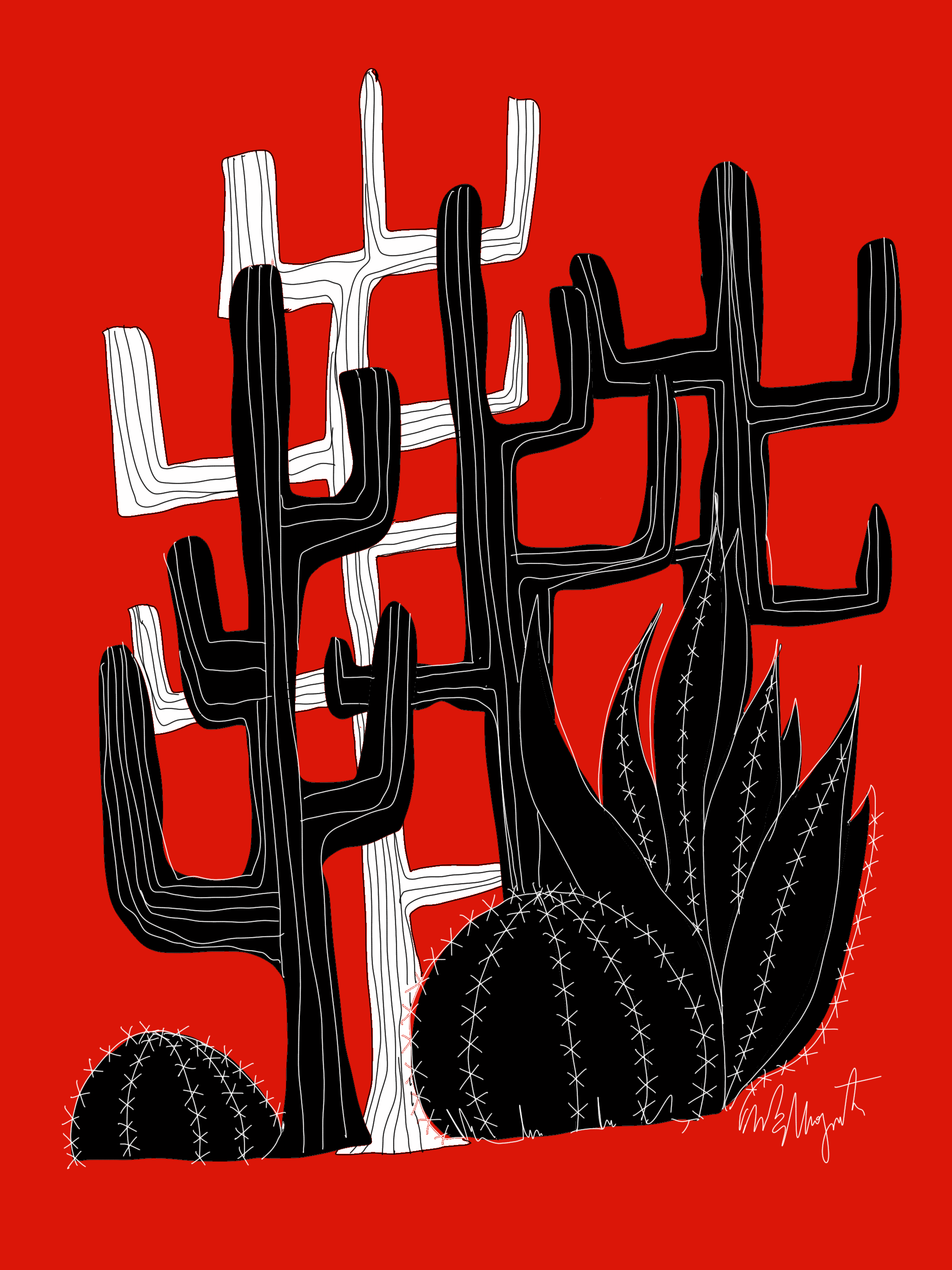

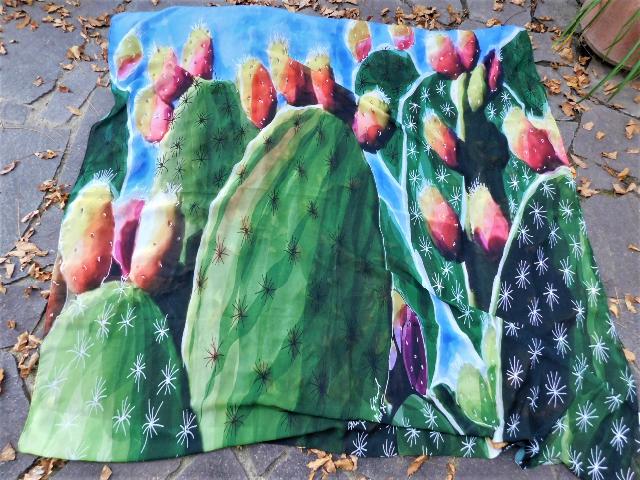

Succulents, cacti, agaves, are not afraid of the places they live and patiently adapt to the weather.

Cacti, succulents, agaves, prickly pears.

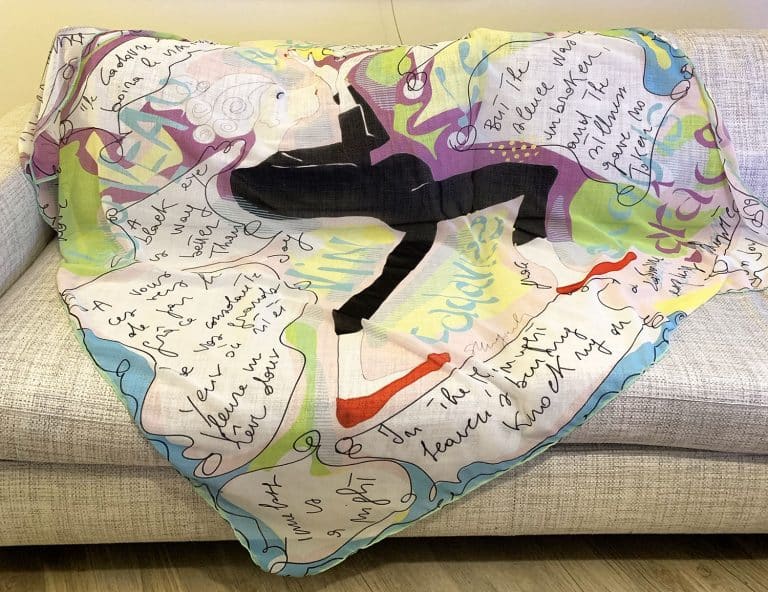

Whatever name we give them, in our imagination they are thorns upon thorns, spiraling spines, sumptuous fruits and flowers, and hot, so hot. For days, for months, for years.

The soil discolors, wears away, becomes sand. And the more the soil fades, the more they sport emerald greens, aqua greens, acid greens.

The sun blinds them, but they remain unperturbed, continuing their existence with a rhythm of growth that is impossible for us to sustain even with our thoughts.

Sometimes they survive us, becoming majestic guardians that bear witness to distant times.

They remain still to act as a backdrop to the changing landscape and mysteriously continue to live even without us.

Heat, silence, wind, humidity are indispensable.

And solitude.

Their calm, if the atmospheric conditions are happy, makes quantum leaps that unhinge the slowness to which we have always been accustomed.

Suddenly they grow, multiply, bloom. They occupy space between stony ground lacking any nourishment, or in the cracks of crumbling and crumbling walls. Witnesses of a glorious past, perhaps, but now completely destroyed.

In the devastation of space, they recreate composed, geometric, ordered gardens. They prop up the crumbling with thorny arms, they support the remaining beauty by exalting it or hiding it behind shovels and branches.

They reconstruct vegetable cities that heal desolating human wounds.

And in spite of these dizzying, improbable growths on hopeless land and houses, they grow mockingly self-sufficient.

When you least expect it, while they seem unchanging, perhaps dead, certainly impassive, here come the blooms that are impressive, scenic almost noisy.

But they last only a few hours, like a show that gives the best of itself because who knows if it will be repeated.

Or they devise another stratagem: they bloom at night, when the sun does not illuminate them. Fragrant, enormous, in great quantity.

No one sees them, they enjoy themselves with no other spectator but their other companions.

It is an audience of the elect and as such, they will enjoy a unique show.

Their leaves are fat, succulent, fleshy.

Or rigid, vertical, thin, like sharp daggers.

Every branch, every blade, every arm is crowned with thorns, needles, hairs, like hairs crystallized in the vapors of heat.

The desert plants have dark colors as if they were shading themselves, self-sufficient.

And they follow a cadenced, mathematical rhythm of forms.

Turgid and tense, they store the water that comes from the morning dew, from the humidity of the night. Mysterious reservoirs like vegetable veins, underground soft bones that support mucilage, precious internal branches like drainage canals.

A whole baroque hydraulic system inside the stems that we can’t even imagine.

But it exists and irrigates the body of the plant, heedless of the high temperatures and scarcity of rain.

They defend themselves from attacks with harmonious and geometric spines and consistent downy hairs.

Succulents, cacti, agaves, are not afraid of the places where they live and patiently adapt to the weather.

The forms depend on the natural function of defense and survival: they are born from simple, elementary structures: spirals that expand, fractals, Fibonacci echoes.

From a cactus to its flower, to the planets in the sky. Everything in nature has a mathematical order.

We, the cactus, the universe.

And even when they adapt as living sculptures in an inauspicious environment, the mathematical order of growth does not lose the rhythm of its composition.

To every prickly pear shovel its neat thorns, to every cactus its new asymmetrical arm, to every juicy petal a new plant identical to its mother, only in miniature.

In survival, they cultivate an austere, logarithmic, essential opinion of themselves.

From Apulia to Sardinia, they dot the space, inventing every month of the year to survive.

Because periods of great drought, where even the humidity of the night evaporates in a great hurry and it is difficult to capture it with the thorns – which are the real leaves – with the roots that are sometimes on the surface to capture the water, correspond to periods of torrential rains, where the end awaits for too much water.

Death is part of life every single moment: dying from too much water, dying from lack of water. And in between, ingenuity to learn to adapt and exist in the best way possible.

I lived in places where the sun screamed for many hours during the day.

Islands in the middle of the sea, peninsulas south to Greece.

Different winds, different lights, different humidity.

In each place, the sun made a truly egregious, vertigo-inducing racket.

But as in every extreme place, it was enough to observe nature to understand how to live.

To take shelter in silence from the attacks of the heat, not to waste energy, to create a barrier to protect oneself, to reflect the light, to build shade and penumbra, to whisper so as not to waste body water, to look everywhere for water and to reserve it.

The scorched and sunny areas of the south where I have lived all maintain this geometric, sober, decidedly rigorous beauty.

Cathedrals in vegetation that welcome the new inhabitant unaware of so much effort.

And the latter, as I myself have experienced, is scrutinized and put under scrutiny.

Because nothing is simple, even the most basic form requires care and respect, silence.

And time and much constancy.

The cactus is a part of the character of the South: patient in its waiting, economical in its consumption, able to adapt, persevering, impassive in difficulties.

A deep and imperturbable quiet that brings plants and people together.

And both mitigate life and harsh, indolent landscapes in the fleetingness of life, ours, in the almost eternal impassibility, theirs.