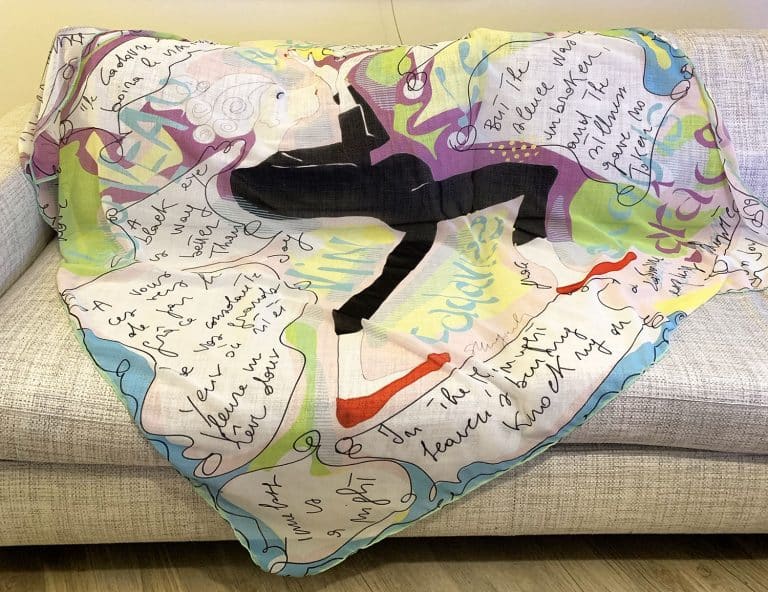

Another story embellishes the column short stories about my scarves, written by writers who love what I do.

Alessandra Zenarola was born and lives in Udine, Friuli.

She made her debut in 2003 with the novel The Vanilla Cowboy, published for Montedit. Later she published the collection of short stories Smagliature (Edizioni del Sale, 2008) and the novels Un cuore di latta (La Caravella, 2010) and L’autunno dell’anno prima (Scrittura & Scritture, 2014), now in a new edition for Solfanelli. With Solfanelli has already published Bassa marea (2016) Il posto più freddo del mondo (2017) and Il solito niente (2019).

Her stories, finalists or winners of literary competitions, are present in collective anthologies.

(If you want to read the story in Italian, click HERE)

*****

Gazing from behind the dirty train windows, time moves faster.

Concentrating on the still-arid fields dotted with small brick homes, the gates a rotten green colour and a doghouse.

Under the beating rain, the meandering line of cars waiting at the traffic light project the evening’s first headlights on the asphalt.

This is what autumn‘s like, the light changes suddenly – day becomes night like a bolt of lightning.

It’s been raining since dawn, water striking the glass and sliding away.

Detail. The whole evades her, she falls in love with detail. Like a nose, the mole under her breast. A gutter hanging from a roof.

The cars halted, a yellow strip sticking out of the car door. A trapped scarf.

It happened to them too, when they left for the summer holidays loaded with suitcases, bags and hat boxes, and on arriving they saw that the light sweater for the cool evenings was all wrinkled, with a sleeve sticking out of the boot.

Too absent-minded, all of them. The train never arrives, it crosses the endless suburb, and the explosion of satellite dishes open like thousands of parachutes above balconies of cracked flowerpots and broken dishwashers.

At the station, the usual group clustered in front of the timetable of arrivals and departures. The cafeterias emanate the smell of pastries and roasted coffee beans and on the escalators, umbrellas hooked to arms are swinging.

It’s a pity that the neon lights paint faces yellowish and they all seem jaundiced.

They say it’s Italy’s most beautiful station. Monumental, quite elegant. Who knows what the others are like. Outside, Milan is buried under the rain, transparent buildings shine in the darkness and traffic proceeds slowly.

She called a taxi, not feeling up to facing the dazed and dripping humanity on a bus or the underground. You’re crazy, he would say to her as a welcome, taxis here cost a fortune.

She couldn’t rid herself of a provincial mindset. In Milan you go by bike and public transport, buy yourself a bomber jacket with a hood and if it’s windy wear a coloured scarf.

Right. A nice scarf like the one sticking out of the car waiting at the traffic light.

It’s curious, he too always mentions that she concentrates on details. Of a passenger immersed in his newspaper she remembers the wrinkle beside his eye, of the lady beside him her skin-coloured stockings, the big Gothic ring of the girl in the miniskirt. Of the waiting car, she wouldn’t be able to describe its shape, its colour or how many passengers it could carry. Only that piece of yellow cloth, waving like a flag.

Who did that handkerchief belong to? To a little girl? They’re the ones who wear clothing as bright as an ice lolly. Or to a woman who mixed up the seasons and thinks it’s still spring?

He grunts, sometimes he gets tired of hearing fantasies. She’s capable of constructing an epic on a cigarette butt still smoking in an ashtray.

For two hours she’s been inventing the day of the woman with the yellow scarf, where she works, what her fiancé’s name is, if she likes Parmigiano cheese on her pasta.

You should have been a storyteller, you know?

She even dreams about her. A pretty woman with straw-blonde rebellious hair. One of those who even wears yellow underwear, or yellow socks under her slacks.

Milan awakes rainy under a sky of milk that offers no opening.

She drinks her third coffee, unwillingly. No train today, housework.

He went out at eight, in an uncertain mood. I’ll be back late he said, already at the door.

A day in slippers and wrinkled tracksuit, computer whirring and the translation to be delivered by Sunday.

She smokes, from the ajar window comes the not yet cold air of the end of October.

It’s almost six o’clock and it stopped raining a quarter of an hour ago. Scooters are growling in the street.

It would be a real boost in life to go out now, put on my warm jacket and boots and stroll along the street without buying anything, just window-shopping and watching people ordering aperitifs and phoning friends to meet for the happy hour.

Milan on Wednesday.

That’s the title of her novel, if she ever gets to writing it. Hackneyed, maybe. Who would be interested in what happens in Milan on a Wednesday? Nothing happens. A woman, neither sad nor happy, is shut up in a work room in chenille slippers translating short stories from Romanian.

And tic-tic, striking the keys and her thoughts wandering elsewhere. Nibble on a biscuit, pour a glass of prosecco, the yellow scarf dances in front of her eyes.

What are you doing? working? he asks over the phone.

Actually, I’m just fooling around. I glance at the news on line.

Suburban tragedy.

Whoever makes up headlines should get a prize for schizophrenic synthesis.

A tragedy is the centre, a circular gust.

Sentences overlap inside the computer. She must have climbed up to the top floor, come out onto the terrace where the residents hang out their sheets to dry and at night the cats meow at the moon.

An ordinary woman driving a car of undefined colour who loves yellow scarfs. There was also a child in the car, but she didn’t see him.

She held the child tight and jumped off.

Milan on Wednesday.

******

(If you want to read the story in Italian, click HERE).